The Root Cause of Lithium Metal Battery Failure: Is It Really Electrolyte "Dry-Out"?Introduction

- Technical Research

- Oct 8, 2025

- 3 min read

To achieve higher energy density, using a smaller amount of electrolyte ("lean electrolyte") in Lithium Metal Batteries (LMBs) is an inevitable trend. However, a well-known phenomenon persists: the less electrolyte used, the shorter the battery's cycle life. The industry has traditionally attributed this to the continuous consumption of the electrolyte during cycling, leading to a depletion of charge carriers—the so-called "dry-out" theory.

However, a recent study from the Helmholtz Institute Münster and the University of Münster in Germany challenges this conventional wisdom with a series of clever "process of elimination" experiments. The findings suggest that the true root cause of failure may not be the depletion of the bulk electrolyte, but rather a "local dry-out" and deactivation of the lithium metal anode itself.

Ingenious Experiments to Trace the Origin of Failure

The research team first confirmed a key phenomenon: when a battery reaches its end of life (EOL), nearly all "lost" capacity can be fully recovered by applying a long-duration constant voltage step. This proves that the capacity fade is primarily caused by a sharp increase in the cell's internal resistance (kinetic limitation), not a permanent loss of active lithium.

The team then conducted two pivotal "component swap" experiments to pinpoint the source of this increased resistance:

Re-wetting with Electrolyte: Injecting fresh electrolyte into the EOL cell only partially restored its capacity. If a simple lack of electrolyte were the sole cause of failure, this should have fully recovered the performance.

Replacing the Lithium Anode: Keeping the old cathode and electrolyte, but replacing the cycled anode with a fresh piece of lithium metal, restored the battery's capacity almost completely to its initial value.

This body of evidence clearly points to the lithium metal anode itself as the primary culprit for failure, rather than an overall deficit of electrolyte.

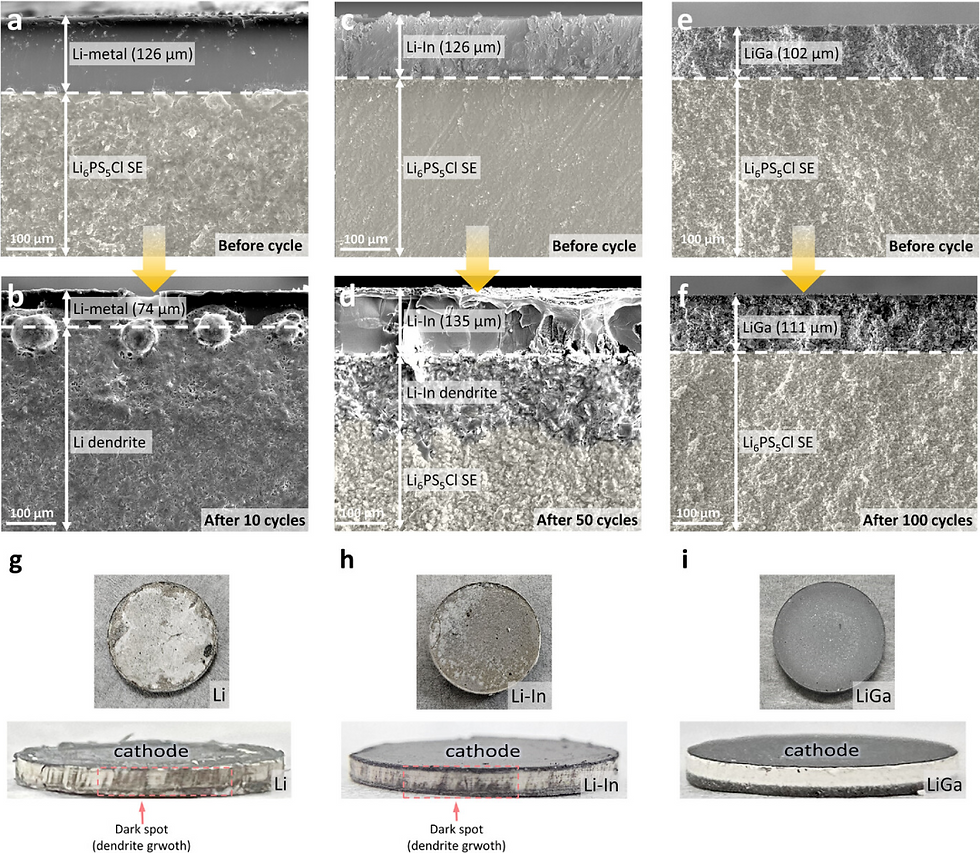

The New Failure Mechanism: "Local Dry-Out" and "Pore Clogging"

Based on these findings, the research team proposed a new failure model centered on the "local dry-out" and "pore clogging" of the lithium anode:

Under lean electrolyte conditions, lithium tends to deposit in a porous, mossy, high-surface-area morphology. The electrolyte is wicked into these tiny pores and is rapidly consumed locally, forming a "dried-out" SEI and "dead" lithium. These products then clog the pores, disconnecting the deeper active lithium from the electrolyte and drastically reducing the electrochemically active surface area.

This reduction in active area creates a vicious cycle: the local current density on the remaining active sites skyrockets, which in turn accelerates the growth of more porous lithium and "dead" lithium. This leads to complete surface blockage, an exponential rise in internal resistance, and sudden cell death.

Conclusion & Design Implications: From "Topping Off" to "Strengthening the Foundation"

This research clearly indicates that the critical failure in lean-electrolyte LMBs is not the depletion of the total electrolyte volume, but the reduction of the effective active surface area of the anode due to porous deposition and pore clogging.

This conclusion provides a vital insight for high-energy-density battery design: rather than simply adding excess electrolyte (which sacrifices energy density) to prolong life, a more fundamental solution is to improve the lithium anode itself from the start. Achieving dense, uniform lithium deposition and building a stable, efficient passivation interface (SEI) are the core strategies to reduce electrolyte consumption, suppress "local dry-out," and thus develop long-lasting, high-energy, lean-electrolyte batteries.

Achieving effective lithium metal protection and dense deposition is key for next-generation battery technology. In this arena, LIMX Power has achieved a key breakthrough, having now mass-produced and commenced bulk deliveries of the industry's first all-silicon-carbon anode battery.

Literature Information

Dominik Weintz, Lukas Stolz, Marlena M. Bela, et al., Isidora Cekic-Laskovic,* and Johannes Kasnatscheew*, Origin of Faster Capacity Fade for Lower Electrolyte Amounts in Lithium Metal Batteries: Electrolyte “Dry-Out”?, Adv. Energy Sustainability Res., https://doi.org/10.1002/aesr.202500233

Comments